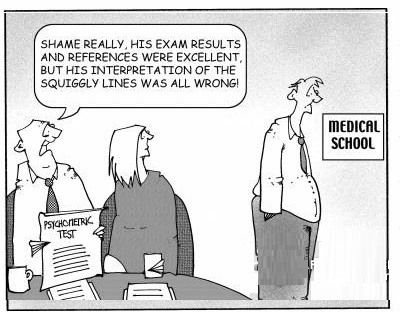

Psychometrics: HR meets hocus pocus

On their first day at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry (Rowling, 1997), each pupil dons The Sorting Hat. Since the school was founded, Godric Gryffindor’s hat has administered a battery of personality tests, intelligence tests, aptitude tests, morality tests, and organisational fit indices to determine which of the four houses would be best suited to that pupil. The Legilimency (Rowling, 1997) of the Sorting Hat is the wizarding equivalent of HR psychometrics, only less opaque.

There are now as many personality tests as you’ll get spam emails this week, and they’ll all promise to reveal your true tendencies and never to sell your data. The structure of most tests is the same, and can be traced back to when Myers met Briggs in the 1920s who came up with lots of forced-choice questions to align with four principal psychological functions. It’s all impressively logical, but largely bunkum. Psychometrics, which roughly translates as soul-counting, can be applied to any psychological capacity, and can measure of lots of types of intelligence, from emotional to numerical reasoning. The whole purpose is to put a number on some aspect of a person, and to put everyone’s number on a scale in order to tell whether you’re good, bad, or indifferent when compared to everyone else.

Behind the magic

It can be useful to know a bit about how these scales are constructed and scored before you start to believe anything about the “results”. They start with a single statement about a personality trait, for example, asking whether the respondent is like that. The simplest responses are Yes and No, but that leaves us with a situation where the world is divided between the Yeses and the Nos. Adding a second question allows for more variability: two Yeses, two Nos, and two combinations of Yes and No. Now we can divide the world into four groups. The more items and the more responses the greater the variance that can be measured, until you end up with something like a normal distribution with very few people at the extremes and most somewhere around the middle.

There are a couple of inherent problems with psychometrics; some people acknowledge these and move on while others just ignore them. Firstly, the phenomenon of social desirability suggests that people will give the answer they think is expected of them. In other words, people lie on self-report measures. Imagine an assessment tool for anger in a job application process and consider how many people will tick Yes for “When angry do you strike out at whoever or whatever makes you angry?” Secondly, psychometrics depends on the respondent’s self-awareness and people aren’t all that good at reaching the kinds of insights demanded by some questions.

More seriously, we seem to find it easier to cope with a small number of categories than a long scale, so it’s common to chop up the scale again and to identify thresholds between groups. That’s a shame after going to all the trouble of putting everyone on a long scale in the first place. These categories are considered a useful administrative tool and can be used, for example, for eliminating a lot of people quickly. However, if you simply exclude everyone who scores below would-run-though-walls-for-manager on the Commitment and Dedication subscale you might just be losing some really good people.

Change is possible

The most serious problem with theories of personality, any attempt to measure personality, and most attempts to measure any psychological characteristic, however, is that the things being measured are assumed to be absolute, that they point to some immutable truth about one’s soul. In fact, they are designed as relative and normative: A scale is only as true as the sample from which the standards are generated, a sample that is taken at a particular place and time, so over time and in different places the norms change. What’s more, people change, so even if you score 137 on an IQ test today there’s no guarantee that you’ll do as well next week, or next year. Psychometrics contributes to the general perception that we’re basically stuck the way we are, which it’s why so many people find it hard to actually contemplate change and so surprising when they do.

Psychometric tests looks like magic: It starts with a string of meaningless words, followed by pained expressions, and – hey, presto! – “You are a Type A worrier with a wing in ‘Enthusiast’ and the perfect set of skills to be a statistician.” In HR, the quest is for the perfect way identify who is the best person for the job. However, tomorrow’s answer to today’s question might be different, but by then you’ll have someone in your house who should really be in Slytherin and you’ll be wondering what’s wrong with your Hat.

Related posts:

Sign up to receive our weekly job alert

Featured Jobs

Higher Education Funding Council for Wales (HEFCW)

Cardiff, South Wales

May 19, 2024

Armagh Observatory and Planetarium

Armagh, Northern Ireland

May 17, 2024