That’s just so meta: Data about data

“Sir, I think you should see this.” Imagine an 18th Century sorting office, musty and dusty with leather-bound ledgers in which were meticulously scratched with quill and ink the dates, senders, and receivers of letters. Mr Braithwaite has discerned a pattern in the correspondence of Ms Catherine Mossday. Today, she wrote to her dressmaker, a florist, and her sister, as well as four times to Mr Brown of Dover Place, Kent Road. Lord Mossday also wrote to Mr Brown, and sent a telegram to The Times. “I think an engagement is set to be announced, sir.” “Excellent work, Braithwaite. Send Mr Brown our list of jewellers, Lord Mossday reviews of banqueting halls, and Ms Mossday that wedding fair pamphlet.”

It has always been possible to record data about how people communicate, but it used to be a bit slower. On the positive side, it was also safer. It is illegal in the US and A to open letter post, or snail mail as they call it. Enacted in 1948, Title 18 of the United States Code provides for a fine or imprisonment for anyone seeking to “pry into the business or secrets of another” by opening a letter, postal card, or package not addressed to them. The same provision does not apply to email, text messages, interweb chat-rooms, and, presumably, blog posts. That means there’s a bot somewhere reading this post about bots reading post. That’s so meta.

Just because we can

Ink and quills are quite inefficient at recording information but computers are very good, and it’s possible to record every click you click and key you stroke in a log file. The clicks and keystrokes correspond to behavioural processes and sequences of actions that can give information on how you interact with, for example, a website. Metadata includes things like time-on-site, time to first action, frequency of action, whether you click a link, and whether you make a purchase. Web development frequently uses A/B experimental designs to compare versions of the page and measure differences user interaction on these metrics.

Every time you do something on a computer or mobile phone, you create data. Because personal data are becoming increasingly valuable and our capacity to store them increasingly large, those devices record lots of information that people either ignore or are unaware of. For example, word processors have metadata on a document’s author, date created, and date modified. It’s really obvious that you’ve cogged your essay when the author isn’t you. Geocodes on photographs occasionally cause concern about the risk of identifying where children live and play. Mobile phone companies tend to be on the frontline of metadata debates. The argument goes that recording metadata isn’t the same as recording conversations; it tells them who you are, where you are, to whom you’re talking, and when but – crucially – not what you’re saying, so it’s not really spying. Privacy concerns aside, there have been some high profile murder cases that stood or fell on mobile phone location data so there is a public-good argument to be made for collecting metadata.

What statistics can do about it

It would probably take a couple of years to collate the hundreds of letters sent between Ms Mossday and Mr Brown during their courtship, and by then they’d be married so it wouldn’t matter anyway. If you’re going to spend time and energy finding out about them, you’d better have a good reason. Even when it’s easy to collect and analyse masses of data, it’s important to identify the desired outcome. The aim is to determine what constitutes a ‘successful’ interaction with your website, identifying optimal sequences of action to make it easier for users to get what they’re looking for, for example. Likewise, common mistakes can be identified and eliminated.

After establishing an outcome measure, some theorising is required to figure out what exactly a particular style of interaction with a site means. It should then be possible to categorise interaction styles, to look at each group separately based on their interactions, and to make different provisions for them. The input of behavioural science can be valuable in figuring out what you want people to do, how to measure whether or not they’re doing it, and matching log file datapoints to discrete actions. Methodologically, measurement of gaze using eye-tracking technology is now central to user experience research.

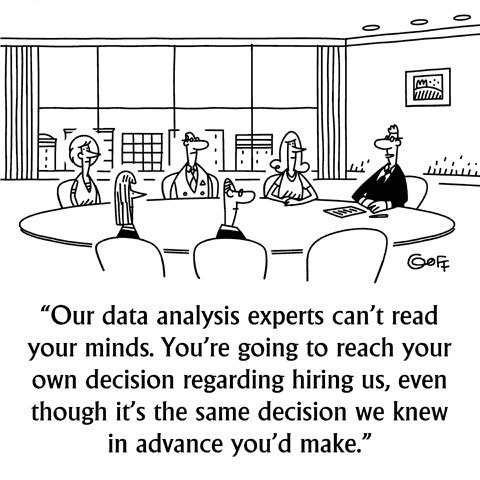

Debates about the morality and legality of metadata collection and storage will be aired elsewhere. The reality is that these data are available and it’s interesting to explore their potential. The problem with log files is the same as any other type of big data: too many numbers, not enough time. What statistics can do about it is use the theoretical and analytical tools available to make sense of all those data about data. Most importantly of all, we can all share in the joy of seeing Ms Mossday and Mr Brown united by technology.

Related posts

Descriptives – 20th February 2015

Efficiency – 15th August 2014

Big data – 30th Mary 2014

Sign up to receive our weekly job alert

Featured Jobs

Cabinet Office

London, Glasgow, Leeds, Manchester, Newcastle upon Tyne, Sheffield, York

February 26, 2026

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Apply before 11:55 pm on Monday 9th March 2026

Bristol, London, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, York

March 09, 2026

Regulator of Social Housing

Birmingham, Bristol, Leeds, Manchester

March 01, 2026

King's College London

London, UK

March 15, 2026

Metronomia Clinical Research

Remote United Kingdom

February 25, 2026